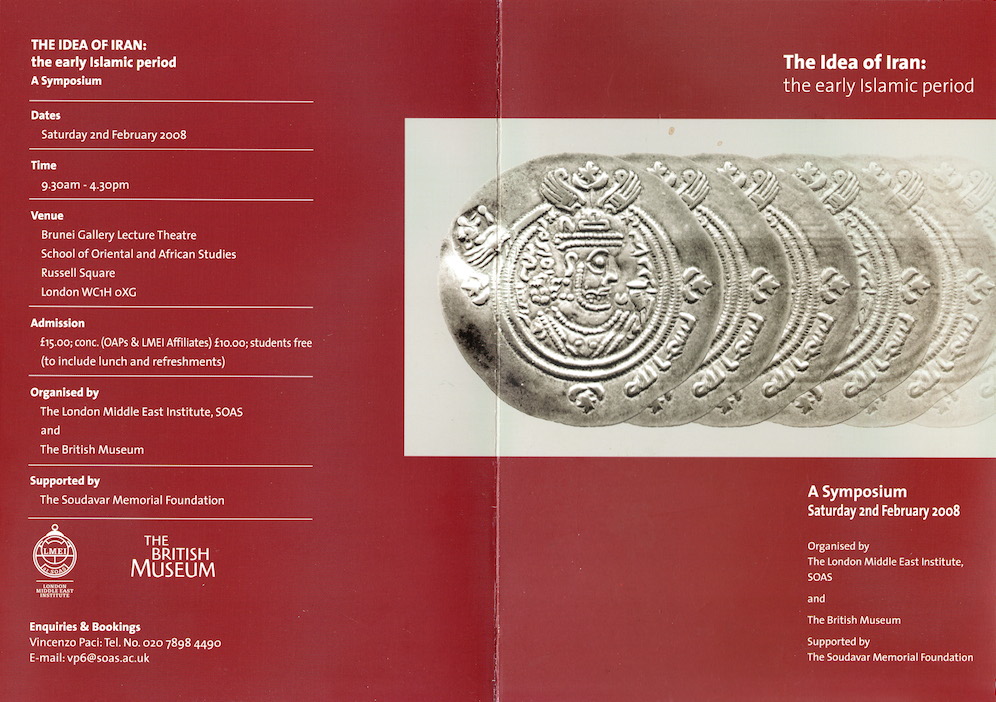

The Idea of Iran: The Early Islamic Period

he fifth in the series of ‘The Idea of Iran’ was held as a one-day symposium at which contributions by seven eminent scholars covered aspects of the early Islamic period.

Convenors

Dr Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis is Curator of Middle Eastern Coins at the British Museum and is responsible for its collection of pre-Islamic Iranian coins (from the third-century BC until the middle of the seventh-century AD), which includes both Parthian and Sasanian coins. She also looks after coins of the Islamic world beginning with the Umayyad and Abbasid periods and including coins of the Samanid and Buyid, Seljuk, Mamluk, Ayyubid and Fatimid, Ilkhanid and Timurid, Safavid and Qajar dynasties. Projected have included The Sasanian Coin Project, a collaborative project with the National Museum of Iran in Tehran, and now successfully completed. The result is a two-volume Sylloge of Sasanian coins of the third- to seventh-centuries AD while Dr Sarkhosh Curtis currently jointly-directs the International Parthian Coin Project, The Sylloge Nummorum Parthicorum (SNP), and is Joint Editor of the SNP series. This multi-institutional project will record Parthian coins of the third-century BC to the third-century AD found in London, Vienna, Tehran, Paris, Berlin, and the American Numismatic Society, New York.

Dr Sarah Stewart is Lecturer in Zoroastrianism in the Department of the Study of Religions at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and Deputy Director of the London Middle East Institute, also at SOAS. She has been co-convenor of the ‘Idea of Iran’ symposia since its inception in 2006 and has co-edited five volumes in the ‘Idea of Iran’ publication series with I.B.Tauris. She serves on the Academic Council of the Iran Heritage Foundation and has been a longstanding Fellow of the British Institute of Persian Studies, most recently serving as its Honorary Secretary until 2013, in which year Dr Stewart co-organised the acclaimed exhibition: ‘The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination’. Her publications include studies on Parsi and Iranian-Zoroastrian living traditions and is currently working on a publication (in collaboration with Mandana Moavenat) on contemporary Zoroastrianism in Iran.

Speakers

- Ehsan Yarshater

- Hugh Kennedy

- Edmund Bosworth

- Richard Bulliet

- Lutz Richter-Bernburg

- James Russell

- Robert Hillenbrand

Iranian Identity after Conversion to Islam

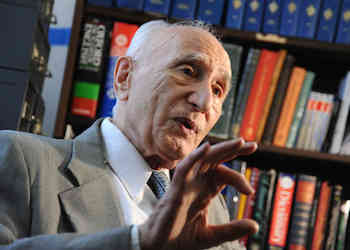

Ehsan Yarshater, Director, Centre for Iranian Studies, Columbia University

Islam, like Zoroastrianism, is a religion that concerns itself not only with the spiritual aspects of life, but embraces and legislates for all other aspects of life. Therefore, conversion to Islam brought profound changes, social, cultural or otherwise, in Iranian society. One could easily expect that Persia, fully occupied and ruled by the Arabs for at least 200 years after the Arab conquest, would change its identity from Persian to Arab as all other countries in the Middle East and North Africa had, such as Iraq, Syria, and Egypt, each of which were heirs to brilliant ancient civilizations. But this did not happen. Persia, while adopting the Islamic religion kept its Persian identity, primarily through tenaciously sticking to its language and thereby to the canons of its distinct culture. Three hundred years after the Arab invasion, the poet Ferdowsi crystallised the Iranian true sentiment with regard to the Persian identity in his immortal Shahnameh, a reminder to Persians of their long and glorious history, their splendid kings, their outstanding warriors, and the great nation that the Iranians had been. His work became symbolic of a dichotomy that characterises Persian history. The question is why Persian proved an exception to the norm?

Why is Iran Not an Arab Country?

Hugh N. Kennedy, Professor of Arabic, SOAS

This paper discusses the reasons for the survival of the cultural and political identity of Iran through the Muslim conquests of the seventh-century. A contrast will be drawn with Syria and Egypt where the pre-Islamic culture was marginalised and the pre-Arabic languages effectively disappeared from common use. It will show how ‘Iranianness’ survived both in the semi-independent principalities which survived the conquests and among the officials and bureaucrats of the Islamic caliphate. It will finish by considering the Shahnameh as a sign of the emergence of New Persian as a language of high culture.

The Persistent Older Heritage in the Medieval Iranian Lands

C. Edmund Bosworth, Former Professor of Arabic Studies, University of Manchester, and Honorary Professor, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter

Continuity of tradition with the pre-Islamic past can be traced in governmental attitudes and practices and, in some instances, a continuity of personnel from Zoroastrian past to Islamic present in the post-conquest period (i.e. after the seventh-century C.E.). Despite a tradition amongst Muslim rigorists that “Islam cancels the past”, there was in several Iranian ruling lines an attempt to establish links, real or imagined, with the pre-Islamic past. Thus the Samanids of Transoxiana and Khurasan, sprung from the dehqan class, had a genealogy provided for them that went back to the father of the Sasanid ruler, Bahram Chubin. Various petty dynasties of the Caspian coastlands and the Elburz mountains interior, themselves comparatively lately Islamised, traced their roots back, with considerable plausibility here, to local pre-Islamic families. Eulogists of the Daylami Buyids connected them with the Sasanid ruling institution while even a power in as late as the twelfth and thirteenth-centuries, the Ghurids, coming from an obscure and backward part of central Afghanistan, managed to find roots in the heroic, legendary, national Iranian past.

Social and Economic Life in Early Islamic Iran

Richard W. Bulliet, Professor of Middle Eastern History, Columbia University

The three-and-a-half centuries that followed the Arab conquests of the seventh-century C.E. witnessed profound changes in the social and economic circumstances of the region that is today circumscribed by the boundaries of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Conversion to Islam is the most obvious of these changes, but conversion was directly linked to economic changes and to urbanisation. Economically, the growth of a cotton industry gave Iran for the first time in its history a major export product. This presentation will describe the evidence for a cotton boom in early Islamic Iran and show how it was linked in to the spread of Islam, the growth of cities, and a cultural efflorescence that made Iran the most important region of the Islamic caliphate. It will also show how this economic dynamism waned in the eleventh-century, partly due to climatic deterioration, leading within a century to a significant shrinkage in iran’s economic and cultural importance.

Quiddities, Algorisms, Oranges-Iran in Islamic Science and Beyond

Lutz Richter-Bernburg, Professor in Islamic Studies, University of Tübingen

In the course of a few centuries, a pluriethnic and plurireligious civilization of extraordinary vibrancy developed under the aegis of, initially, Arabian Islam in the vast swathe of territories encompassing Western Asia and North Africa. Not the least achievement of this civilization was the pursuit of science and learning beyond any utilitarian consideration and shared among all religious, linguistic and ethnic segments of the population. Thus it is of little wonder that the people of Iran, one of the most numerous constituent groups among caliphal subjects, were notably involved in related activities as well. Indeed, several of the most prominent figures of a wide range of disciplines including, but not limited to, medicine and auxiliary fields, mathematics and astronomy, philosophy, and even Arabic grammar, hailed from Iran. Some of them became household names even beyond the boundaries of their own civilization. Names that spring to mind include Sibawayh, al-Khwarizmi, Rhazes, Haly Abbas, Avicenna, al-Biruni, to mention but a few, and where applicable, in their medieval Latin form. In this presentation, these and numerous others will be situated in their respective cultural and disciplinary context, including the subsequent reception of Islamic learning in the Latin West.

The Cross and the Lotus: An Armenian Miscellany

James R. Russell, Mashtots Professor of Armenian Studies, Harvard University

The medieval Armenian collection of didactic tales and precepts, Zroyc’ pinke k’alak’i, “Tale of the City of Brass”, which exists in MSS and in numerous printed editions even down to recent years, includes such Persian and Islamic material as the counsels of Anushivan and the legend of King Bahlul, as well as the Wisdom of Ahiqar and local hagiographies. In various respects the book’s organisation, literary form, and unifying themes suggest a close analogy to the Buddhist Saddharmapundarika Sutra (Lotus Sutra of the Good Law). This text in its turn reflects the conventions of storytelling and aesthetics of Iranian Central Asia.

What Happened to the Sanian Hunt in Islamic Art?

Robert Hillenbrand, Professor of Islamic Art, University of Edinburgh

This lecture focuses on a textile which can be shown to be no later than the early ninth-century and which re-uses a familiar theme of Sasanian court art – the royal hunter. It is a test case of the many ways in which early Islamic artists copied, grappled with, misunderstood and popularised the Sasanian heritage. Analysis will reveal how the original meaning is gradually lost as the image shrinks in size, is duplicated or even quadrupled, acquires extra detail or suffers crucial iconographic degradations. A similar process of transition can be demonstrated in other media, such as metalwork and pottery, but costly textiles travelled across wider distances and with greater ease; hence echoes of this theme can be found as far afield as China and Western Europe. Such textiles document the busy afterlife of Sasanian themes in the most unexpected guises.