Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture & National Heritage

his is a guide to a juncture in Iranian history when foundational issues of national purpose and cultural heritage – secular reform and religious tradition – were being reframed. Architecture of the Pahlavi reign, 1925-79, is the principal subject of discussion, along with the Society for National Heritage, which commissioned numerous buildings and monuments, initiated over sixty preservation projects, and founded the nation’s first archeological museum and its first national library. The broad scope of analysis sheds new light on how and why Iran’s cultural heritage was reinvented and used as a corridor to a progressive and at times utopian modernity; as an ideology for political reforms; and as a platform for claims to a leadership role in international politics.

Revolution and tradition are two sides of the same coin in Talinn Grigor’s book on Iranian architecture. It starts in 1925 after Reza Pahlavi seized control of the country, but it arcs back to Ancient and Medieval Persia. Not that the government was rejecting modernity. It instead promoted a reconstruction of the past that would aid efforts to make modern Iran an independent nation with an irrefutable claim to existence and power. Prodigious archival research informs Grigor’s account of the excavations and discoveries Iranian authorities used to construct monuments to national heroes like Omar Khayyam, an important mathematician and astronomer of the 11th century as well as the author of the ‘Rubauyat’. Grigor also brings immense knowledge to her lively discussions of the modern idiom integrated into such retrospective monuments and buildings. Illustrated, this book introduces architecture and historical sources that are all but unknown outside specialist circles. It is the first in English to study twentieth-century Iranian architecture within the historical contexts that shaped its from and significance. The corpus of photographs will help the many readers unfamiliar with the architectural riches of Iran. Current turbulence and misunderstanding with the Middle East highlight the importance of Grigor’s book.

Dr Talinn Grigor (Ph.D., MIT, 2005) is an Associate Professor of modern and contemporary architecture in the Department of Fine Arts at Brandeis University. Her research concentrates on the cross-pollination of architecture and (post)colonial politics, focused on Iran and India. Her first book, ‘Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture, and National Heritage under the Pahlavi Monarchs’ (Prestel, 2009) examines the link between official architecture and heritage discourses in 20th-century Iran. ‘Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio’ (Reaktion, 2014) explores Iranian visual culture through the premise of the art historical debate of populist versus avant-garde art that extends into the identity politics of the exile. A co-edited book with Sussan Babaie, entitled ‘Persian Kingship and Architecture: Strategies of Power in Iran from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis’ (I.B. Tauris, 2014), investigates the architectural legitimisation of royal power through Iran’s long history. Her present project deals with the turn-of-the-century European art-historiography and its links to eclectic-revivalistic architecture in Qajar Iran and the British Raj.

Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture, and National Heritage is a remarkable account of Iranian modern history. Architecture played a crucial part in this history: it was a major political tool in re-appropriating Iranian cultural heritage alongside secular reforms during the Pahlavi monarchic rule of Reza Shah (1925-41) and his son Mohammad Reza Shah (1941-79). The book highlights the pivotal role played by the Society for National Heritage (SNH), established in 1922, in executing a major modernist architectural overhaul in Iran. The SNH was responsible for commissioning various monuments and buildings throughout Iran, which included mausoleum style tombs for Iran’s treasured poets such as Ferdowsi, Hafez and Omar Khayam, the first archaeology museum and first national library, as well as various architectural preservation projects. The aim of this utopian and large-scale architectural facelift was to fast-track Iran into the twentieth century. It embraced Iran’s epic cultural history as well as its penchant for progressiveness by adopting Aryan modernist principles.

In Building Iran, Talinn Grigor makes explicit the knowledge and history that has so far remained only amongst privileged circles, and deconstructs Iran’s complex architectural history through a close analysis of its reconstructed monuments. She (re)evaluates how the Pahlavi’s zeal for modernization and the SNH’s projects attempted to deconstruct monumentality by rebuilding pre-existing architectural sites and erecting new monuments on which to project utopian ideologies and secular traditions. The movement to entice the masses away from religion towards civil pilgrimage was an important goal of the Pahlavi’s and SNH’s missions, and Grigor highlights that this was achieved by looking back at Iran’s glorious pre-Islamic era.

An important example is the designing of the mausoleum of Ferdowsi, the poet and author of the tenth-century national epic, the Shahnameh (book of kings in Farsi), to celebrate Ferdowsi’s millenary anniversary in 1934. The building functions as a booster of national pride based on the Shahnameh’s representation of ancient Iran. Ferdowsi’s tomb was initially designed by French architect and archaeologist André Godard (1924-34) in Tus and became known as Ferdowsiyeh with its distinctive pre-Islamic design and Zoroastrian ornamentation. Ferdowsiyeh contributed to fabricating a sense of modernism by becoming a touristic site, where Iranian families performed modern past-times such as picnicking and taking day trips. Grigor points out that it was plagued with several design problems; that it was already sinking into the ground in 1934 and was considered a symptomatic example of Reza Shah’s hasty desire for rapid reform. Yet Ferdowsiyeh took 43 years to fully complete, with Iranian architect Houshang Seyhoun finishing its design in 1968. It came to represent – somewhat paradoxically – Reza Shah’s invented history. However, unlike the case of Ferdowsiyeh other projects conducted under the auspices of the SNH were more efficient as Grigor meticulously details.

Although Building Iran takes a critical stance towards the tenure of the Pahlavi era it does offer a particularly rewarding chapter, Masculinist Myths of Modernism, which analyses how the power shifted organically from the Shah and the SNH during the 1970s to the queen. Farah is represented as an admirable model, who established several cultural centres and chaired all national and international cultural and arts related affairs. Within the chapter, Grigor interweaves Farah’s story alongside an analysis of American born art historian and Persian art expert Phyllis Ackerman. Ackerman’s husband was Arthur Pope, an acclaimed historian, professor and consultant to Mohammed Reza on Persian art – his legacy, like that of Reza’s, was largely upheld by his wife. Grigor portrays both Farah and Phyllis as highly feminist figures, the real ‘architects’ who shaped art and society, as Grigor states, ‘through the agency of ‘mere art’, Queen Farah in politics, and Ackerman, in academia, exercised power over their respective mainstreams. While Farah and Ackerman could not (and would not) prevent a revolution, they did question and exasperate the masculinist strictures of culture, modernity, and politics that defined the Iran of the 1970s.’

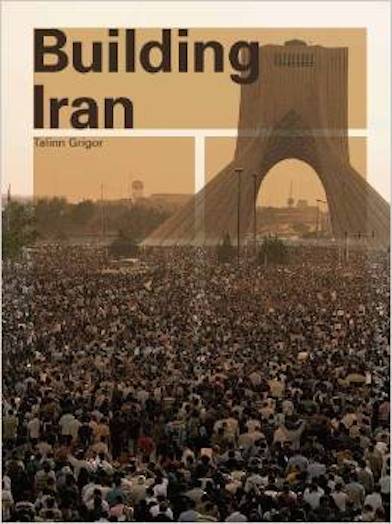

While Building Iran is largely a study of twentieth-century architectural history it does give an inadvertent clue to Iran’s twenty-first-century future, coded within the cover art, which pictures a defiant scene from the 2009 election protests. The image features hundreds of protesters in Tehran with the city’s famous Shayad Aryamehr monument dominating the landscape, a building designed by Hosayn Amanat (1971-74) to mark the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire and renamed Azadi (freedom in Farsi) in 1979 after the Iranian Revolution. The choice of this epic vista suggests that the future history lies in next generation of Iranians – these ‘informal architects’ who have spurned a global outcry are at the cusp of becoming the rightful custodians in (re)building Iran.

Sara Raza is a PhD candidate at the Royal College of Art, London, an independent curator, editor for ArtAsiaPacific Magazine (West and Central Asia) and editorial correspondent for Ibraaz. She is head of curatorial programmes at Alåan Artspace in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and associate curator at the Maraya Art Centre, Sharjah. Since 2010 she has been a visiting lecturer at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, for the Masters Contemporary Art programme. She is a former curator at Tate Modern, South London Gallery and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin and has curated, lectured and published internationally.