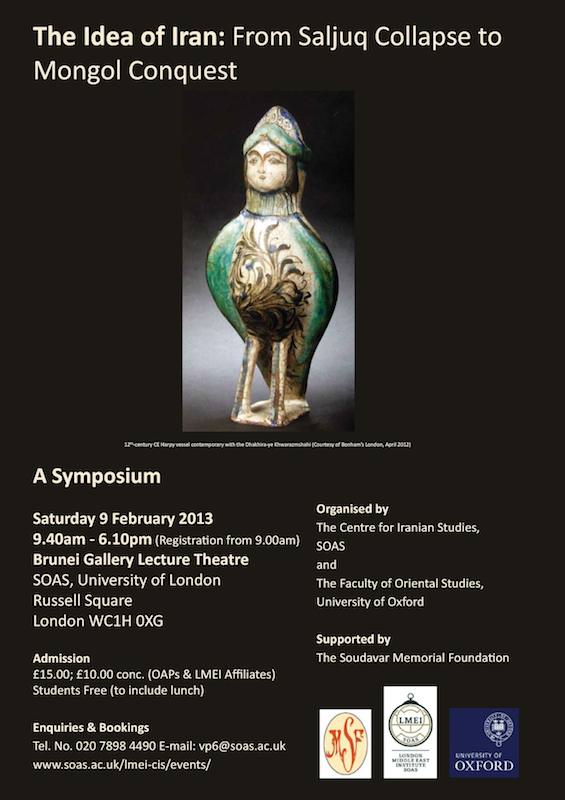

The Idea of Iran: From Saljuq Collapse to Mongol Conquest

fter the death of Sultan Sanjar in the mid-sixth/twelfth-century the Saljuq empire rapidly unravelled, its provinces fragmenting into a patchwork of mostly short-lived principalities and kingdoms. This was the era when the atabegs – originally guardians responsible for the upbringing of Saljuq princes – developed into a series of independent local dynasties, each holding a fig-leaf of legitimacy in the shape of a Saljuq puppet prince. After a time new powers emerged: the pagan Qara-Khitai, in Central Asia; the Khwarazmshahs in Khwarazm, Khorasan and much of central Iran; to the southeast the Ghurids, who contested Khorasan with the Khwarazmshahs while ruling much of Afghanistan, Sind and the Punjab. All of these were blown away by the Mongol conquest at the start of the thirteenth century, an event which contemporaries present as a veritable cataclysm. Neither the breakdown of imperial power and centralized government, nor even the Mongol catastrophe, prevented Persian literature from flourishing: Anvari, Khaqani, Nezami, Attar, Rumi and Sa’di all belong to this period, while other arts and sciences also continued to find patronage.

In this the tenth Idea of Iran symposium, we will explore the complex political dynamics of this age – up to the second Mongol invasion under Hulegu in the 1250s and the establishment of the Il-Khanid state – and will focus also on its extraordinary literary, scientific and cultural achievements.

Speakers

- Edmund Bosworth

- Alka Patel

- David Morgan

- Michal Biran

- Hormoz Ebrahiminejad

- Christine van Ruymbeke

- Homa Katouzian

- James Allan

The Anushteginid Khwarazm Shahs: Gentle Ascent and Catastrophic Fall

Emeritus Professor Edmund Bosworth, Visiting Professor at the Centre for Middle East and Islamic Studies, Exeter University

This dynasty of Shahs, in effect the last of a line of Iranian and then Turkish rulers of Khwarazm in Central Asia (now falling essentially within the Uzbek and Turkmen republics), held power there as vassals of the Great Saljuqs, but increasingly in name only from the later eleventh century. In the second half of the twelfth century they built up a powerful military empire extending from Khwarazm and Transoxania in the east to north-western Iran and the Transcaucasian region in the west, only for this rapidly to collapse in the early thirteenth century under the onslaught of the Mongols.

The Periphery as Centre: The Ghurids between the Persianate and Indic Worlds

Dr Alka Patel, Associate Professor, Department of Art History, University of California, Irvine

The short-lived Ghurid empire occupies an ambiguous historiographical locus, and throws into relief the power of hindsight in evaluating the differing significance of a polity according to time and place. In the medieval Persianate world of greater Iran (encompassing modern Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia) the Ghurids were a short-lived minor dynasty that, according to learned opinion, did little to change or even contribute to Persianate culture. They were based in the isolated central areas of modern Afghanistan and extended only as far west as Herat. Towards the east, however, the Ghurid armies campaigned into northern India, bringing large swaths of it under an Islamic political power for the first time.

The Mongols in Iran, 1219—1256

Professor David Morgan, Former Professor of History and Religious Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Iran was not fully incorporated into the Mongol Empire until Hulegu’s expedition, which began in 1256, but the country had felt the Mongol impact from the time of Chinggis Khan’s invasion of the Khwarazm Shah’s empire in 1219-1223. This paper will explore the Mongol impact on Iran during the period between the two invasions, and the nature of Mongol rule in parts of Iran at that time. In recent years historians have, justifiably, pointed to the previously undervalued positive features of Mongol rule. But these came into play, effectively, from the time of the establishment of the Ilkhanate as a stable polity in the late 1250s. Prior to that, the Mongol invasion was initially catastrophic, though the ground was in some ways laid for a more benevolent future which was to be dominated, until the 1330s, by Hulegu and his descendants.

Scholarship and Science under the Qara Khitai (1124—1218)

Professor Michal Biran, The Max and Sophie Mydans Foundation Professor in the Humanities, Director, The Frieberg Center for East Asian Studies, Institute of Asian and African Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

In the twelfth-century a Manchurian people expelled from north China established in Central Asia the Qara Khitai or Western Liao dynasty. This “infidel” dynasty ruled over a mostly Muslim population in a rare harmony. Moreover, the relative stability and prosperity that the Qara Khitai brought to Central Asia enabled the flourishing of Islamic and “secular” scholarship under their rule. By following the careers of twelfth and thirteenth- century scholars, including migrants from the Qara Khitai realm who were active under Mongol rule, this paper reconstructs the main fields of knowledge and achievements of Central Asian scholars under the Qara Khitai and the impact they had on the later Islamic world, including Iran.

Isma’il Jorjani’s Zakhira-ye Khwarazmshahi: Towards Vernacular Medicine

Dr Hormoz Ebrahimnejad, Lecturer in the History of Modern Iran and the History of Medicine, University of Southampton

Following the translation of Galenico-Hippocratic medicine into Arabic, the major reference sources in the Islamic world were written in Arabic, such as Avicenna’s Canon and Razi’s Continent. Jorjani’s Zakhira might be considered as an attempt to assert Persian scientific authority in an Islamic empire, in line with the revival of the Persian language and culture, represented by Ferdowsi’s Shahnama. In this paper, I test the hypothesis that the Zakhira represented the process whereby Humoral medicine was adopted by local populations, just as the medicine of the Prophet indicated that Humoral medicine had been assimilated into religion. Vernacular medicine (medical texts written in Persian) did exist before Jorjani but a reference text book such as the Canon, or Havi’s calibres was lacking. The Zakhira filled this gap.

Nezami’s Giant Brain: Poet, Scholar, Rewriter

Dr Christine van Ruymbeke, Soudavar Senior Lecturer in Persian, University of Cambridge

This presentation will examine the artistic achievement of Nezami of Ganja, probably one of the most intelligent figures in the history of literature. His talent as a poet is undisputed and recognised by anyone who has been in contact with his divan, or most probably his collection of six (!) masnavis, collectively called the Khamsa. In today’s presentation I will explore two facets of this compelling artist. First I will look at the evidence found in his verses of a solid grounding in, and whimsical game with, the multiple scientific knowledge of his time, with which he plays elegantly in order to titillate the audience, and I will next examine what becomes of the Shahnama plots and stories he used in four of his masnavis, showing how he manipulates the older poet’s work.

Sa’di on Love and Morals

Dr Homa Katouzian, Iran Heritage Foundation Research Fellow, St Antony’s College and Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford

What is certain about Sa’di’s life is that he flourished in the thirteenth century (seventh century hijra), went to the Nezamiya College of Baghdad, travelled wide and lived long. It is clear from his love poetry that he was an ardent lover, and from many of his works that he was not a Sufi, although he cherished the ideals of Sufism and admired the legendary classical Sufis. He was also a teacher of manners and morals. There is a humanist tendency in his works which is remarkable as it was another two-and-a-half centuries before the emergence of Christian humanism in Europe.

Inlaid Metalwork in Iran in the Twelfth to Early Thirteenth Centuries

Professor James Allan, Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East

In spite of the political uncertainties, the quality of inlaid metalwork produced at this period in Khurasan, and particularly in Herat, is outstanding. The forms and colour schemes of the objects suggest the transfer of craftsmen from silver to base metal, but the main source for the decoration must have been manuscript illumination and illustration, even though the relevant manuscripts are no longer extant. From inscriptions on particular objects comes the first direct evidence of the craft industry, and of the members of the middle class who commissioned the pieces.

Convenors

Professor Edmund Herzig holds the Soudavar Chair in Persian Studies at the Oriental Institute and is a Fellow of Wadham College at the University of Oxford. He received his BA in Russian and Persian from the University of Cambridge and his DPhil in Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford. His thesis was entitled ‘The Armenian Merchants of New Julfa, Isfahan: A Study in Pre-Modern Asian Trade’. His principal research interests are the contemporary history of Iran (currently focusing on the political and international history of the Islamic Republic, and on the relationship between history and national identity in modern Iran); Safavid history; the history of Armenia and the Armenians with special interest in the Armenians of Iran. Recent publications include ‘The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity’, with M. Kurkchiyan (2005); ‘Regionalism, Iran and Central Asia’ in International Affairs (2004); ‘Venice and the Julfa Armenian Merchants’ in B. L. Zekiyan and A. Ferrari eds. ‘Gli Armeni e Venezia’.

Dr Sarah Stewart is Lecturer in Zoroastrianism in the Department of the Study of Religions at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and Deputy Director of the London Middle East Institute, also at SOAS. She has been co-convenor of the ‘Idea of Iran’ symposia since its inception in 2006 and has co-edited five volumes in the ‘Idea of Iran’ publication series with I.B.Tauris. She serves on the Academic Council of the Iran Heritage Foundation and has been a longstanding Fellow of the British Institute of Persian Studies, most recently serving as its Honorary Secretary until 2013, in which year Dr Stewart co-organised the acclaimed exhibition: ‘The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination’. Her publications include studies on Parsi and Iranian-Zoroastrian living traditions and is currently working on a publication (in collaboration with Mandana Moavenat) on contemporary Zoroastrianism in Iran.